The Barcode Scanners

Somewhere in the last two years, a remarkable transformation occurred in academia and publishing. Professors and editors — the very people whose entire professional value proposition rests on their ability to read, comprehend, and evaluate writing — stopped doing that. They replaced it with something far more efficient: pattern-matching.

Not the good kind. Not the kind where a seasoned editor recognizes that an argument's structure has quietly collapsed under the weight of its own unsupported premises, or where a professor detects that a student has papered over a gap in understanding with confident-sounding filler. No. This is the kind where a grown adult with an advanced degree and institutional authority scans a student's paper or a submitted manuscript, spots the word "delve," notices a suspiciously well-organized heading structure, clocks a transition sentence that feels a little too smooth, and declares — with the confidence of a man who has just dusted for fingerprints at a crime scene — that artificial intelligence has been detected.

The process, if one can dignify it with that word, works roughly like this: acquire a list of words, phrases, structural patterns, and formatting tendencies that large language models allegedly favor. Note that the prose is "too clean." Observe that the paragraphs follow a consistent internal logic — topic sentence, supporting evidence, synthesis — as though coherent organization were itself suspicious. Flag the use of transitional phrases. Flag the balanced sentence structure. Flag the fact that the piece doesn't meander, doesn't lose its thread, doesn't exhibit the kind of chaotic, half-formed argumentation that apparently signals authentic human effort. Treat this collection of heuristics as though it were peer-reviewed forensic methodology rather than what it actually is, which is a glorified internet rumor with a spreadsheet and a bias toward punishing competence. Upon locating enough matches, skip the tedious business of evaluating whether the writing is any good, whether the argument holds, whether the evidence supports the thesis, whether the author demonstrates genuine understanding of the subject. Why bother? The paragraphs were too well-structured. The transitions were too seamless. Someone used "moreover" and organized their thoughts logically. Case closed. Call the provost.

What makes this particular brand of intellectual collapse so spectacular is who's doing it. These aren't people who wandered in off the street and were handed a red pen. These are credentialed professionals whose one job — the skill that justifies their salary, their title, their authority over other people's careers and grades — is the ability to critically evaluate text. And they have, with breathtaking efficiency, replaced that skill with a parlor trick. They have voluntarily surrendered the single competency that distinguishes them from a Scantron machine, and they appear to be proud of it.

One might reasonably ask: if your method for evaluating writing doesn't require you to actually evaluate writing, what exactly are you being paid for?

We'll get to that. But first, let's talk about where the sacred list came from.

The Snitch List

The tell lists — and let's use that term loosely, since "list" implies a level of rigor these collections have not earned — come from a variety of sources, nearly all of which share one delightful characteristic: they are themselves products of the very technology they claim to detect.

Here's how the sausage gets made. Someone — a blogger, a professor with a Twitter following, an "AI literacy" consultant who materialized out of nowhere around 2023 with a Substack and a mission — sits down and asks ChatGPT some version of the following question: "What words and phrases do you use most often?" The model, being an obliging next-token predictor with no particular reason to lie about its own tendencies, produces a list. "Delve." "Tapestry." "It's important to note." "Nuanced." "Straightforward." "Navigate." The questioner copies this output, formats it into an article or infographic, and publishes it as a diagnostic tool. Other people share it. Professors print it out and tape it next to their monitors. Editors bookmark it. An entire detection methodology is born, and its founding document is a conversation with the suspect.

Let that sink in for a moment. The forensic framework that these professionals are using to accuse writers of secretly using AI was generated by AI. They asked the machine to snitch on itself, took its word for it without a shred of independent verification, and then built an enforcement regime around the snitch list. This is the investigative equivalent of asking a suspect to write their own wanted poster and then using it to identify them in a lineup. It is not, by any reasonable definition, a methodology. It is a horoscope with academic pretensions.

But it gets better — or worse, depending on your tolerance for irony. The lists didn't stop at vocabulary. They expanded, as such things always do, into structural and stylistic tells. AI-generated text, the hunters declared, tends toward certain organizational patterns: consistent paragraph structure, clear topic sentences, balanced argumentation, logical flow from point to point. It favors enumerated lists. It employs transitional phrases that connect ideas smoothly. It avoids sentence fragments and abrupt tonal shifts. It tends to hedge appropriately rather than making wild unsupported claims.

Read that list again. Slowly. Now ask yourself where you've seen those characteristics described before.

If you answered "every writing guide, style manual, and composition textbook published in the English language in the last century," congratulations. You have identified the problem that the tell-hunters have not.

What they have assembled, with great ceremony and confidence, is a list of the characteristics of competent formal writing. The traits they're flagging as artificial are the same traits that their own institutions have been explicitly teaching, demanding, and rewarding for decades. The five-paragraph essay structure they drilled into students? Suspicious. Clear transitions between ideas, the thing they circled approvingly in red pen for years? Evidence of machine involvement. Well-organized arguments that proceed logically from premise to conclusion — the entire stated purpose of academic writing instruction — now constitute probable cause.

The call is coming from inside the tenure-track house, and the person who answered the phone is too busy highlighting instances of "furthermore" to notice.

There's a secondary layer of absurdity here that deserves attention, if only because the hunters themselves seem magnificently unaware of it. Many of these same professors and editors have enthusiastically adopted AI-powered detection tools — GPTZero, Turnitin's AI detection module, Originality.ai, and their various competitors — to supplement their word-hunting with what they believe to be technological rigor. They are, in other words, using AI to catch AI. They have deployed algorithmic pattern-recognition to identify algorithmic pattern-generation, and they are treating the output of this process as though it were evidence rather than what independent testing has repeatedly shown it to be: a coin flip with a confidence score attached.

The false positive rates on these tools are not a secret. They have been documented, published, and discussed extensively. They are particularly brutal for non-native English speakers, for writers who learned English in formal academic contexts, and for anyone whose natural prose style happens to overlap with the statistical center of the training data — which is to say, anyone who writes the way universities have been teaching people to write. None of this has meaningfully slowed adoption. The tools provide what the tell-hunters crave: the appearance of objectivity without the inconvenience of judgment.

So let's inventory what we have. A detection methodology built on lists generated by the technology it claims to detect. A set of stylistic red flags that are indistinguishable from the characteristics of good writing. Automated tools with documented failure rates being treated as forensic instruments. And presiding over all of it, professionals whose defining qualification is critical analysis, who have at every stage of this process declined to critically analyze anything.

This would be funny if it weren't destroying people's grades, careers, and reputations. Which brings us to the core of the matter.

The Algorithm Calling the Kettle Black

Let's state the central irony plainly, because it deserves to be pinned to the wall and examined in good light.

The AI-tell hunters have positioned themselves as the last line of defense for human critical thinking. They are the guardians of authenticity, the sentinels at the gate, the brave few willing to stand between civilization and the oncoming tide of machine-generated mediocrity. This is the narrative they have constructed, and they believe it with the fervor of people who have never paused to examine whether their own behavior is consistent with their stated mission.

It is not.

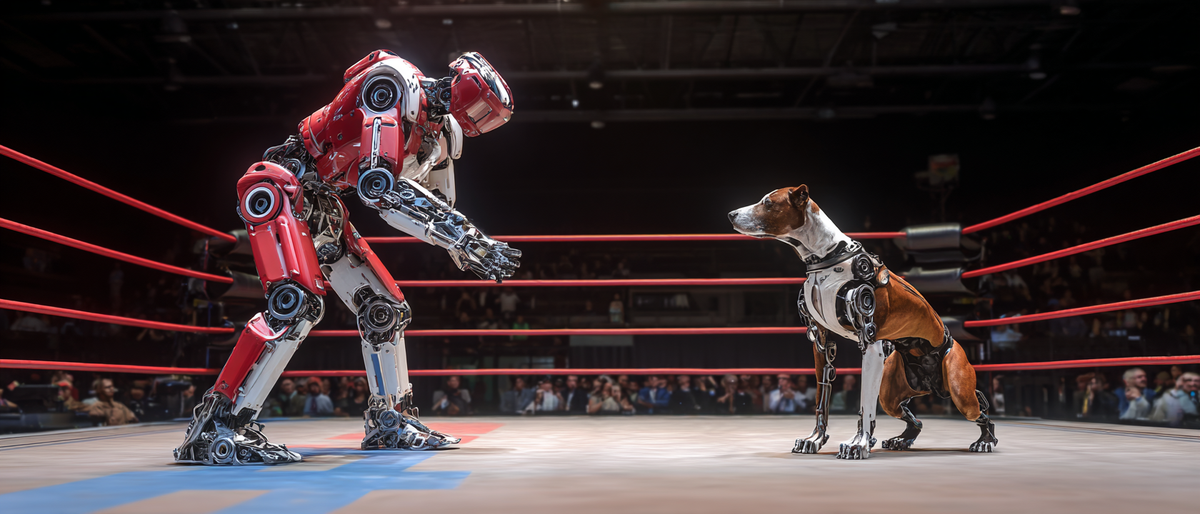

What these defenders of human thought have actually done is build an evaluation process that requires no human thought whatsoever. Their method is entirely mechanistic. Scan for flagged words. Check for structural patterns that match a template. Run the text through a detection algorithm. Tally the results. Render a verdict. At no point in this workflow is anyone required to understand what the text says. At no point does anyone need to assess whether the argument is original, whether the analysis demonstrates genuine comprehension, whether the writer has engaged meaningfully with the source material, whether the conclusions follow from the evidence presented. The entire operation can be — and increasingly is — performed without any intellectual engagement with the content at all.

They have, in the most literal sense available, automated their own critical thinking. And they did it while lecturing everyone else about the dangers of automated thinking. The irony isn't subtle. It isn't hiding. It is standing in the middle of the room wearing a fluorescent vest, and they are stepping around it on their way to flag another instance of "furthermore."

Consider what a genuinely human evaluation of writing looks like. A professor who is actually doing their job reads a student's paper and asks: Does this person understand the material? Have they engaged with the complexity of the topic, or are they skating across the surface? Is the argument internally consistent? Does the evidence support the claims? Are there moments of genuine insight — the kind that suggest a mind actively wrestling with an idea rather than reproducing someone else's conclusions? Can the student, when questioned, defend and extend what they've written?

These are hard questions. They require expertise, attention, and time. They require the evaluator to have actually read and thought about the submission. They cannot be answered by ctrl+F searching for "delve."

Now consider what the tell-hunters are actually doing. They are looking at the container and ignoring the contents. They are evaluating the surface characteristics of text — word choice, sentence rhythm, organizational patterns, formatting tendencies — while making no effort to evaluate the substance. This is not a minor procedural shortcut. This is the wholesale abandonment of the skill they are paid to exercise. An English professor who evaluates writing by scanning for vocabulary patterns is a mechanic who diagnoses engines by looking at the paint color. They may occasionally stumble into a correct conclusion, but not because their method has any relationship to the problem they claim to be solving.

And here's where the irony sharpens into something genuinely damning. The entire critique of AI-generated text — the legitimate critique, the one worth making — is that it can produce fluent, well-structured prose that sounds competent without necessarily being substantive. That it generates text that looks right without the underlying comprehension that makes writing genuinely valuable. That it privileges surface over substance. Form over meaning. Pattern over thought.

This is exactly what the tell-hunters are doing.

They have adopted a method of evaluation that privileges surface over substance, form over meaning, and pattern over thought. They are guilty of precisely the intellectual failure they claim to be policing. The only difference is that when an LLM produces superficially competent output without genuine understanding, it has the excuse of being a statistical model with no capacity for comprehension. The professors and editors doing the same thing have no such excuse. They have the capacity for critical thought. They are simply choosing not to use it, because checking a list is faster, easier, and provides the satisfying illusion of rigor without the exhausting reality of it.

One might be tempted to call this lazy, but that feels insufficient. Laziness implies awareness that a harder, better option exists. What the tell-hunters have achieved is something more remarkable: they have convinced themselves that their shortcut is the rigorous option. They believe — genuinely, passionately — that they are doing more work, not less. They are putting in extra effort to catch the cheaters. The fact that this extra effort consists entirely of avoiding the one activity that would actually reveal whether cheating occurred does not appear to trouble them.

The question is not whether the student used AI. The question is whether the professor is using their brain. And at the moment, the evidence is not encouraging.

The Dragnet

There is a particular kind of cruelty in a system that punishes competence, and the tell-hunters have built exactly that.

Consider the non-native English speaker — say, a graduate student from Seoul or São Paulo or Bangalore — who spent years learning formal academic English. Not conversational English. Not the loose, idiomatic, occasionally incoherent English of native speakers dashing off emails. Formal academic English. The kind taught in intensive language programs and advanced composition courses worldwide. The kind characterized by precise vocabulary, careful transitions, hedged claims, and logically structured paragraphs. The kind that, if you haven't been paying attention, sounds exactly like what the tell-hunters have decided AI-generated text sounds like.

This student didn't learn to write by absorbing the chaotic, meandering, stylistically inconsistent habits of native speakers who can afford to be sloppy because nobody questions their humanity. They learned from textbooks and structured curricula. They learned the rules before they learned which rules could be broken. Their prose is clean because they worked brutally hard to make it clean. Their transitions are smooth because they memorized transitional phrases from a handbook and practiced deploying them until the deployment became automatic. Their paragraphs are well-organized because disorganized paragraphs got them failed out of the language program that was their ticket to an international education.

And now a professor with a tell list is staring at their work and thinking: too polished. Too structured. Nobody writes like this naturally.

The professor is correct, in the most obtuse way possible. Nobody writes like this naturally. This student writes like this because they clawed their way to fluency through years of deliberate, agonizing, structured practice. The "unnatural" quality of their prose is the evidence of their effort, not the absence of it. But the tell-hunter doesn't see effort. The tell-hunter sees pattern matches. And the pattern matches say AI.

They are not alone in the dragnet. Accomplished writers with a naturally formal register get flagged. Technical writers whose entire profession demands precision and clarity get flagged. Students who actually absorbed what their composition courses taught — clear thesis statements, logical organization, evidence-based argumentation — get flagged for the sin of having learned what they were taught. The tell-hunters have, with magnificent obliviousness, constructed a system that specifically targets people who write well in the manner that institutions have been explicitly demanding they write for generations.

Meanwhile — and this is where the irony graduates from amusing to genuinely infuriating — the student who did use AI, but used it intelligently, walks through the checkpoint without a second glance. The student who prompted an LLM, received a draft, then spent two hours restructuring the argument, replacing generic examples with specific ones drawn from the course material, injecting their own analysis, cutting the transitional filler, adding a few deliberate imperfections because they'd read the tell lists too and knew what to avoid — that student passes inspection. They "sound human." Their work has rough edges. The tell-hunter nods approvingly at the slightly awkward sentence in paragraph three, finds no flagged vocabulary, and moves on.

So the system catches the diligent non-native speaker who wrote every word themselves, and clears the savvy native speaker who used AI as a drafting tool and edited strategically. It punishes the wrong people for the wrong reasons while missing the very behavior it was designed to detect. This is not a flawed system that needs tuning. This is a system that is structurally incapable of achieving its stated purpose, because its stated purpose — identifying AI-assisted writing — has nothing to do with the only question that actually matters: is this work any good, and does the person who submitted it understand it?

But asking that question would require reading the work. And we've established how the tell-hunters feel about that.

Your Actual Job

Let's dispense with the gentle suggestions. This is not a section about what professors and editors might consider exploring as alternative approaches to the complex and evolving challenge of AI in writing. This is a section about what their job already is and has always been, and about the fact that they have simply stopped doing it.

If you are a professor, your job is to evaluate whether a student understands the material and can think critically about it. That's it. That is the entire mandate. You are not a process auditor. You are not a workflow investigator. You are not a detective tasked with reconstructing the exact sequence of keystrokes that produced a document. You are a person whose professional obligation is to assess comprehension, analytical ability, and intellectual engagement. You have always had the tools to do this. They are called "reading the work" and "talking to the student."

A student submits a paper. It is well-written, clearly argued, and logically structured. You suspect AI involvement because it is well-written, clearly argued, and logically structured — a suspicion that should probably prompt some uncomfortable self-reflection about what you've come to expect from your students, but set that aside. You have options. You can ask the student to discuss their argument. You can probe the reasoning behind specific claims. You can ask why they chose one piece of evidence over another, how they would respond to a counterargument, what they found most difficult about the topic. In five minutes of conversation, you will know whether this person understands what they submitted. No tell list required. No detection software. No forensic vocabulary audit. Just the basic evaluative skill you were hired to exercise.

If the student can defend and extend the work? It doesn't matter how they drafted it. They understand the material. They can think about it. They can articulate and defend a position. The assignment has achieved its educational purpose. Whether they typed every word from scratch, dictated it into their phone while walking the dog, used an AI tool to generate an outline they then rebuilt from the ground up, or wrote it longhand in a cabin by candlelight is entirely irrelevant to the question of whether they learned anything. And whether they learned anything is the only question you were ever being paid to answer.

If the student can't defend the work? Then you've caught them. Not through a word list. Not through a detection algorithm. Through the radical, apparently now countercultural act of engaging with another human being about ideas. And you've caught them in a way that is actually fair, actually defensible, and actually based on evidence of the thing that matters — comprehension — rather than evidence of the thing that doesn't — process.

The same applies, with minor adjustments, to editors. Your job is to evaluate whether a piece of writing is good. Whether it is clear, accurate, original, well-reasoned, and worth publishing. If a manuscript meets those standards, your readers are served. If it doesn't, they aren't. The author's workflow is not your concern. Whether they drafted in Word or Google Docs, longhand or voice-to-text, with AI assistance or without, at a desk or in a bathtub — none of this has any bearing on whether the text in front of you is any good. You are an editor. Edit. Evaluate. Apply the judgment and expertise you spent a career developing. If you cannot determine whether writing is good by reading it, no detection tool is going to compensate for that deficiency, because that deficiency is the problem.

The tell-hunters have executed a remarkable inversion. They have transformed a failure of their own professional competence into an accusation against everyone else. Rather than confronting the uncomfortable possibility that they can't reliably distinguish good AI-assisted writing from good unassisted writing — which, if the assistance was used well, they shouldn't be able to, because that's what good assistance looks like — they've decided that the inability itself is proof that something nefarious is happening. They can't tell the difference, so there must be cheating. The alternative explanation — that there is no difference worth detecting, because the output is genuinely good — does not appear to have occurred to them.

The quality of the output is your business. The process is not. This has always been true. It was true before AI. It was true when students used tutors, writing centers, heavily involved study groups, Adderall, and the accumulated marginal notes of every student who owned the textbook before them. Nobody demanded that writers prove they suffered sufficiently during the drafting process. Nobody required a detailed accounting of which ideas arrived through individual genius and which through conversation, collaboration, or plain luck. The work was evaluated as work. It stood or fell on what it contained.

That standard hasn't changed. The tell-hunters have simply abandoned it, because meeting it requires the one thing they've decided they no longer need to do.

The Last Line of Defense Against Reading

Here, then, is the final portrait of the AI-tell hunter. A professor or editor who has dedicated themselves to the preservation of human critical thinking by eliminating human critical thinking from their own workflow. A guardian of authenticity whose detection method is indistinguishable from the shallow, surface-level, pattern-matching behavior they claim to be fighting against. A professional reader who has found, at long last, a way to stop reading.

They have built an elaborate apparatus — tell lists sourced from the suspect, detection tools with the reliability of a mood ring, structural heuristics that flag the characteristics of competent writing as evidence of fraud — and they have convinced themselves that operating this apparatus constitutes intellectual labor. It does not. It constitutes the avoidance of intellectual labor, dressed up in the language of vigilance. They are not defending standards. They are replacing standards with a process so mechanical, so devoid of genuine analysis, so perfectly automated in its refusal to engage with content, that it could — and this is not a joke so much as a clinical observation — be performed by the very technology they claim to oppose.

The great irony of the AI-tell hunter is not merely that they use AI-generated lists and AI-powered tools to do their hunting. It's not merely that they flag the hallmarks of good writing as evidence of machine involvement, or that their dragnet catches the diligent and clears the strategic. The great irony is that they have made themselves unnecessary. If evaluating writing requires nothing more than scanning for vocabulary patterns, checking structural consistency against a template, and running text through a probabilistic classifier, then we don't need professors and editors to do it. We need a script. A competent undergraduate could automate the entire operation in an afternoon, and the results would be exactly as meaningful as they are now — which is to say, not at all.

The tell-hunters set out to prove that AI could not replace human judgment. They have instead provided the most compelling evidence yet that, in their case, it already has. Not because AI took their jobs. Because they gave their jobs away, voluntarily, and charged themselves with something simpler — something that requires no expertise, no critical faculty, no years of training in how to evaluate whether a piece of writing thinks.

Somewhere, there is a student who wrote something brilliant with the help of an AI tool, and a professor who will never know, because they were too busy counting instances of "moreover" to read it. And somewhere else, there is a student who wrote something brilliant entirely on their own, and a professor who accused them of cheating, because the work was too good and too clean and too well-organized to have come from a human being.

Both of these failures have the same root cause. Both of them end the same way: with a professional who was paid to think about writing choosing instead to think about anything else.

The tools have changed. The job hasn't.

Read the work.

Member discussion: